Blind Spot: Princess Caraboo of Javasu

Thanks you for reading Historical Blindness. This is a fortnightly blog and podcast, and you are reading a Blind Spot installment, which is shorter bonus content I release between my principal blog posts. This Blind Spot happens to be sandwiched between part one and part two of a series on Kaspar Hauser, the mysterious foundling of early 19th century Bavaria. As such, I highly recommend you take the time to read Kaspar Hauser, Part One—Foundling, before enjoying this Blind Spot, which serves as an interlude and bridges the two halves of that story. For this is the story of another foundling—although this one not a child—who appeared in England almost exactly 11 years previously, give or take a month, and one who also excited the sympathies of all who encountered her. She too inspired and even encouraged legends of having been born of royalty in her native land, and this she accomplished without ever speaking a word that could be understood by her adherents. This is the story of Princess Caraboo of Javasu.

*

On an April evening in 1817, in the village of Almondsbury, in County Glocester, a beautiful black-haired woman who looked to be in her mid-twenties appeared at the open door of a reverend’s cottage and made gestures indicating she wanted to come in and rest on the couch. She wore all black—black gown, black shawl, black stockings—and even her eyes were deep black pools. She appeared unable to speak a word of English; beyond her gestures, she expressed herself in a tongue understood by none and was thus referred to the local Overseer of the Poor, who in turn brought her that very evening to the mansion of a local Magistrate, Mr. Worrall, for he was aware that in the household there lived a servant who spoke several foreign languages. This mysterious foreign woman appeared reluctant to enter the mansion, but relented upon the kind invitation of the lady of the house, Mrs. Worrall, who that evening became charmed by the prepossessing young woman and greatly concerned for her well-being.

Mrs. Worrall put her up in a public house that night, where in the parlor the woman pointed to a picture of a pineapple and appeared to indicate she was familiar with the fruit. Some other hints at her country of origin could be gleaned from her unusual customs at the public house and afterwards, during her brief stay at St. Peter’s Hospital as a vagrant. She refused any meat or alcohol, much like Kaspar Hauser would a decade later, taking only tea and preferring rice to bread, seeming in fact to favor a vegetarian Hindustani diet, especially savoring curries. Furthermore, she appeared unfamiliar with traditional beds, needing to be shown how to use them. All of these clues seemed to indicate that she originated from some tropical and perhaps Asian locale, and yet she seemed to adhere to some Christian traditions, praying over her food and at her bedside before sleeping, and showing some recognition of the significance of the cross. Mrs. Worrall, who continued to visit her despite wariness that the young woman might be making a fool of her, spoke to her frankly in English, begging her to come clean and promising to offer her aid regardless of any deception, but the young woman remained impassive, convincing Mrs. Worrall that she understood English not at all. With a little more coaxing and gesturing, she got the girl to share her name, which she pronounced as “Caraboo.”

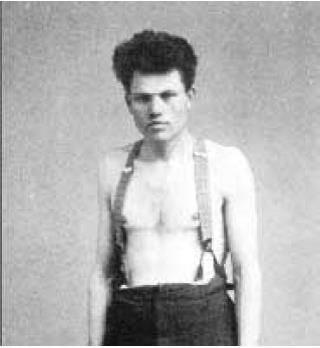

Portrait of Princess Caraboo of Javasu, circa 1817, by Thomas Barker of Bath, via Historical Portraits Image Library

Many people came to visit this Caraboo during her stay at the hospital. They brought books with them in hopes that Caraboo might indicate her place of origin by pointing at a map or picture, while others brought foreign-born visitors they believed might be able to discern Caraboo’s language. Eventually, one such visitor, a Portuguese man from Malaysia named Manuel Eynesso, finally declared the language she spoke to be an admixture of Sumatran and some other Indonesian island dialects, interpreting her words to tell her story in broad strokes, that she was of high birth in her homeland and had been kidnapped from her island, brough across the world to England and abandoned. Upon Eynesso’s word that Caraboo was genuine, Mrs. Worrall insisted that the poor girl return to live at her. Indeed, she became something of an object of curiosity during her stay at the mansion of her benefactress, and men of high pedigree would come to see her and question her for themselves, some of them supposedly learned men, linguists, physiognomists, and craniologists. One among these, a man who had himself made multiple voyages to the East Indies, recorded the particulars of Caraboo’s tale based on his understanding of her tongue and interpretation of her gestures.

By this account, Caraboo was a princess of an island called Javasu, daughter of a Chinese-born chieftain who went about carried by common folk in a palanquin and a Malaysian mother who had been a killed by cannibals. Her own trouble had started when out for a stroll in her royal garden at Javasu accompanied by some ladies in waiting. Pirates ambushed them, bound and gagged them and carried them off to their ship. Too late did her father realize the crime; he swam after the pirate ship and shot an arrow but only succeeded in killing one of Caraboo’s handmaids. Caraboo herself fought valiantly, killing one pirate with a dagger and wounding another, but to no avail. The pirates made good their escape and within two weeks sold her to another pirate captain. This second ship she found herself on appeared to trade in female flesh, as Caraboo described them stopping at ports, acquiring other women as prisoners and then offloading them again at other ports. Eventually, the ship on which she remained a prisoner sailed for Europe. After months at sea suffering at the hands of pirates, she leapt overboard at the first sign of the English coast. Thereafter, she wandered from house to house begging before finding her way to Almondsbury and the charity of Mrs. Worrall.

During her stay of some ten weeks at the Worrall mansion, and despite the suspicions of some who believed her a fraud, Princess Caraboo never once faltered in her character as not only a devout and demure princess but also a fierce and exotic warrior. She presented quite a sight to the Worralls and their guests. Fashioning her own dresses in the style of her culture, with long, wide sleeves and a large band of cloth wrapping her midsection, she went about in a homemade headdress of feathers and flowers, balancing plates of fruit on her fingertips and performing elaborate yet delicate dances unlike any they had seen before, falling to one knee and rising in agile leaps, lifting a foot in a sling and waltzing in strange, contorted ways. On the Worrall estate, she was known to paddle a boat out into the pond or sit in the top of a tree to avoid the company of men. Additionally, she carried a tambourine and a gong on her person, which she struck and rattled as she saw fit, and she made a show of keeping track of time using an odd system of knotted strings. Perhaps most strikingly, she armed herself like a true Disney warrior princess, with a bow and arrow on her shoulder and a sword and dagger at her waist. Nor was she unskilled in the use of these weapons, as she was seen many times to practice with them, and indeed a gentleman somewhat skilled at fencing found himself unable to disarm her.

Princess Caraboo in costume, via Wikimedia Commons

Try as they might, her doubters could not catch her out. One man looked deeply into her eyes and declared in no uncertain terms that she was the most beautiful creature he had ever beheld, but she gave no outward blush or any other indication that she had understood his words. Servants of the household, who perhaps resented the privilege extended to the mysterious girl, contrived to prove her an impostor by lying awake to hear if she talked in her sleep, but she appeared to speak her native language even in her sleep! And when woken suddenly, she never had a slip of the tongue. Indeed, no one ever heard her speak anything other than her strange language, and in this she was consistent as well, with certain words always used in the same manner, meaning the same thing: mosha for man, raglish for woman, pakey for child; night was anna and morning mono; ake brasidoo, she might say, meaning “come to breakfast,” or inju jagoos, meaning “do not be afraid.”

As such an interesting character, it’s no surprise that her story made it into newspapers, and it may also come as no great shock then that, having read about Princess Caraboo in the papers, someone contacted Mrs. Worrall to inform her that her guest was an impostor, a poor girl out of Devonshire named Mary Baker known for her eccentricity and propensity to spin tales. Thus armed with evidence of Caraboo’s imposture, Mrs. Worrall sat her down and confronted her. Caraboo, or rather, Mary Baker, at first attempted to continue feigning an inability to understand Mrs. Worrall, but eventually, she broke down and admitted her deception. She claimed to have previously lived in Bombay as the nurse of a European family and to have come to England after living some time on an island east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean…but this too was discovered to be a lie, and eventually Baker told a truer story, although this one no less shocking for the tragedy therein.

Mary Baker had lived in the village of Witheridge in her youth. She had somewhat of a rebellious temperament, disobedient and ambitious. Her parents more than once arranged employment for her, and she consistently left these positions in dissatisfaction, returning home again. She struck out on her own then, and after finding some work in Exeter, she took her earnings, bought some fine clothing, and again left her position to return home. This time, however, seeing her new clothing, her father accused her of theft, and she left again, becoming a beggar and vagabond. During this miserable time, she seriously considered hanging herself, and was in fact in the process of tying her apron strings to a tree in a deserted country lane to accomplish the act when she believed she heard a voice saying that such an act was a sin against God. Untying her apron strings then, she went about her vagrant life, sleeping in hay lofts and panhandling from house to house, once begging at a constable’s house and only just escaping imprisonment. Finally succumbing to hunger and fatigue, she collapsed and was saved by a passing wagon, the drivers of which took her to London, where some other good Samaritans conducted her to a hospital. There she stayed for months, delirious and being treated for what they styled a “brain fever,” which treatment consisted mostly of cupping, blistering and blood-letting. In her delirium, she considered the nurses to be angels, of whom she daily inquired whether she was dead.

After her hospital stay, she was adopted by a charitable family that taught her to read, but again, after three years of happiness, Mary defied her mistress’s wishes by contriving to make time with a servant cook. After the ensuing falling out, she again left her comfortable circumstances in a headstrong huff, returning to her vagabond’s life before ending up as a housemaid at a convent. However, upon sharing her story in its entirety, she was accused of falsehood—for surely she was a sinful girl and not the unfortunate innocent that she presented herself to be!—and again she was turned out, this time by a minister. Thereafter, due to the dangers of life on the streets and highways, she passed herself off as a man, and it was during this time that she was taken in by highwaymen, robbers who were looking to recruit her as a fellow blackguard. Upon uncovering her true gender, made obvious by the way she cried out when discharging a gun, these highwaymen ended up paying her to keep her silence about their hideout and their crimes. After escaping these criminals, she took a variety of positions in different households, in Exeter and back again, in London. During this time, she claimed to meet a man who married her, took her traveling, and then abandoned her back in London with child. After delivering her baby, she took the child to a Foundling Hospital and asked that they take the baby in, for she had no means of supporting it. Still, she visited the baby regularly, until such time as she learned that the child had taken ill and passed away. Thereafter, she left London for good.

During these most recent years of vagrancy, she fell in with gypsies for an undisclosed period of time, and it was perhaps from these that she learned the trick of passing herself off as a foreigner, for after this time she admitted to going from town to town and from house to house, pretending not to speak any English and thereby exciting the sympathy and charity of almost everyone she encountered. Thus when she arrived at Almondsbury, she was already well practiced in her imposture.

And she certainly had been aided in her pretense, for throughout her narrative, she spoke of people who falsely claimed to recognized her language, which she admitted now was pure gibberish! Some had called it Spanish, and others French. Indeed, Manuel Eynesso, in claiming he recognized her speech as Indonesian, had greatly helped to convince everyone of her veracity, yet all she had done was babble nonsense words, letting others who wished to seem knowledgeable do the rest. It seemed, actually, that most of her story had been invented by those trying to interpret her gibberish and gestures, and that she had merely played along! Remember that the people who visited her and speculated upon her origins and customs did so in clear English, within earshot, affording her the advantage of showing them just what they were looking for. For example, she had actually overheard the servants who conspired to stay up and listen to her in her sleep, so she had remained awake herself and pretended to speak her gibberish language even while sleeping!

Gibberish characters made use of by Princess Caraboo, via Wikimedia Commons

Mrs. Worrall checked on her story, of course, and found it corroborated in almost every detail, except for the detail of who the father of her child had been—he may have been a gentleman who married her and swept her away in travel, or he may have been a day laborer or even the husband of one of the families she had served. Regardless, as Mary Baker, aka Princess Caraboo, had never attempted to bilk her or otherwise misuse her outright and had only stayed at the mansion at Mrs. Worrall’s own insistence, she did Baker one last favor and paid her way to America, where this remarkable and resourceful woman disappeared from history and may have actually continued her impostures here. Indeed, who knows what she might have made of herself…

The parallels between Princess Caraboo and Kaspar Hauser are numerous. They both appeared to be innocent creatures in distress and relied on the charity of strangers. Both displayed unusual eating habits, and both inspired legends of having come from royal lineage, legends that they themselves may have encouraged. It is difficult to make the argument that Kaspar Hauser himself had heard the story of Princess Caraboo and decided to perpetrate a similar fraud, although this is entirely possible. What is rather easier to assume is that the general public had heard the story of Princess Caraboo, for a narrative of the incident by John Matthew Gutch, which I have relied on for this account, appeared the very same year in 1817. This famous story of a false foundling, an impostor passing herself off as royalty, may have contributed to the turning of opinion against Kaspar Hauser, for although the theory that he was a lost prince was rising, so too was the notion that he was a sham.

*

Thank you for reading Historical Blindness. I’ll be back in a couple weeks with the conclusion of my series on Kaspar Hauser. If you liked this installment and are interested in historical hoaxes, charlatans and impostors, you’ll love my novel, Manuscript Found!, about the founding of Mormonism.